Insight by: Steve Martin

Outsourcing has always made for heated politics, as politicians typically equate “outsourcing” with “offshoring.” It’s hard to believe that it’s been 30 years since Ross Perot’s much ballyhooed “giant sucking sound” made for great living room drama in the 1992 presidential debates centering at the time on the North American Free Trade Agreement (even more ironic that Perot was largely “credited” with starting the IT and business process outsourcing industry 30 years prior to that debate – and oh, by the way, making billions from the sale of both EDS and Perot Systems, his two mainstream outsourcing companies…how the worm turns…but we digress).

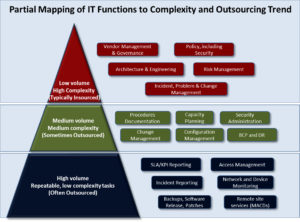

Setting aside the political and commercial rhetoric, whether we like it or not, IT outsourcing has been, and will continue to be part of the core operational model for healthcare organizations for years to come. However, as it pertains to key decisions between what these organizations should outsource and what they should keep or bring back in-house (i.e., “repatriate”), the advice is simple – keep the part above the neck – i.e., arms and legs are fungible, the brain is not. For example, while hospitals can reliably turn over their network and device monitoring to an offshore third party provider, they would be well advised to maintain decisions around their EMR strategy / upgrade path in-house. Similarly, a global pharmaceutical company would likely realize savings without discernible risks when it comes to using an outside provider to install software patches or execute new product releases but ceding control of their cloud strategy and architecture to an outsourcer could have considerable adverse financial and operational impacts on their entire IT operations – with those consequences potentially impacting the environment for years.

Back to a bit more history. As indicated above, the outsourcing of IT services had its roots in the 1960’s and by the mid-1980’s, with the transfer of low complexity IT processes to third parties, essentially to realize the benefits of labor arbitrage, started to become commonplace, particularly for large corporations looking to cut costs. The trend continued through the 1990s and into the new millennium as buyers began expanding their IT outsourcing strategies to include more complex IT processes, enabled through a significant increase in the level and sophistication of competitive alternatives (particularly as the Indian-based suppliers entered the US market) and corresponding improvements in network connectivity between the US/European markets and the remote delivery centers. In some instances, companies underwent wholesale reorganizations and staff reductions, turning over the keys for virtually all operational execution and even strategic decision making to third parties while maintaining only vendor oversight and governance in-house. Fast forward to today, and the decision on what to outsource vs. insource (or repatriate) has become even more nuanced. Outsourcing customers are rethinking the scope of their outsourcing decisions (particularly offshoring decisions) for a number of strategic reasons, chief among them, the considerable increase in the integration of IT services with core customer facing products. The advancement of IT enabled products and capabilities (e.g., precision medicine, MRNA technology, neurotechnology, health wearables) has been occurring at warp speed with no slow-down in sight. This dynamic places a premium on companies actually building in-house IT teams for critical functional areas – not only for the product development itself, but for the critical infrastructure and application development environments that are required to support these products.

Charting a Path Forward and Assessing Insourcing Readiness

Healthcare organization that currently outsource, particularly those that have moved further down the IT value chain with their third party providers, are well advised to routinely undergo a thoughtful examination of whether the outsourcing strategy and value proposition still hold. Companies must rigorously analyze the role and position of its IT function in the organization, particularly with respect to the connectivity with their core product and service delivery strategies, in order to determine whether insourcing could drive increased value. For example, how tightly must IT be aligned with the business on a daily basis to foster product innovation? How much benefit can be gained by being unshackled from a relationship with a third party whose primary goal is to make money – for itself? In the end, companies must be able to discern the difference between the outsourcing “concept” no longer being the right fit versus the specific outsourcing model (or even, the outsourcer) no longer being the best fit, before leaping forward with a decision to insource.

Along with a broad strategy for managing services in-house versus outsourcing, a company must review specific IT functions relative to their suitability for in-house delivery. The following framework illustrates functions that are often performed in-house versus those that are typically outsourced based on their transaction volume and complexity.

If results of the review indicate that partial or full insourcing is the most appropriate future approach (as opposed to re-sourcing to another provider or remediation of the existing agreement), the following considerations should be assessed to determine the feasibility of executing that approach:

- Level of IT Dependency for Core Customer Facing Products and Services – the pace of product and service development, particularly across the life sciences, biotech, pharma, and healthcare landscapes has never been a) greater, nor b) more dependent on IT. Organizations that have outsourced core IT functions must continually evaluate the extent to which control of their various environments is critical to their product/service development strategies – short term operational savings realized from outsourcing can be dwarfed by adverse impacts in product development efficiency and efficacy that can arise when a third party provider is making decisions based at least in part on their own economic interests.

- Total Cost of Ownership and Formalized Business Case – ensuring that a rigorous analysis and comparison of costs for each service delivery model is calculated and packaged according to the company’s financial business case rules on time horizons, discount rates, and other modeling guidelines. For outsourced services, this includes all monthly service charges, project fees, pass-throughs, asset costs, retained organization costs, early termination penalties or minimum revenue / volume commitments, and quantification of missed service levels and rework. For in-house services, this includes the fully loaded transition costs for moving back in-house (recruitment, tools, facility readiness, etc.), fully burdened resource costs (compensation, benefits, facilities, overhead), attrition (ongoing recruitment, training), tools, hardware, software, and facilities.

- Contractual Barriers – ascertaining the extent to which there are definitive requirements for the supplier to provide knowledge transfer, data transfer, tools transfer, and general transition assistance and conversely, determining impediments to transition such as early termination provisions / penalties, and minimum revenue commitments.

- Technical Complexity – assessing the transition and ongoing operational implications associated with the current state technical environment, particularly related to such factors as the level of standardization across the enterprise (e.g., number of PC images, range of hardware platforms currently being supported), diversity of end user requirements, and the pace of operational change required by the business.

- Schedule – developing a realistic estimate of the time required to plan and execute the transition to the insource model and reconciling that timeframe with the current supplier agreements and likely outcomes – in particular, accounting for the contractual implications (e.g., increase in rates, removal of supplier key personnel), loss of future leverage, supplier employee attrition, etc., associated with a transition that extends past the termination date of the agreement or simply takes longer than expected is critical.

- Technology Infrastructure – performing a gap assessment between the current technology infrastructure residing in-house versus that which is needed in an insourced model, including components such as data center/NOC facilities, tools (e.g., monitoring, service desk, CMDB, asset management) and the personnel to manage the environment.

- Space – determining whether there is adequate facility space and the extent to which it can be readily built out to appropriate specifications to house the newly hired staff and hardware/infrastructure in the required timeframe.

- Ability to Attract and Retain Staff – understanding the organization’s ability to attract, hire, and retain talent, particularly related to such considerations as the cache/brand of the company, location where employees would be required to reside, compensation and benefits programs, and training and career advancement programs.

- Human Resource/Recruiting Expertise – assessing the proficiency and capabilities of the company’s HR department in terms of being able to perform recruitment, on-boarding, training, and talent management.

- Transformation Readiness – assessing the company’s capacity for, and ability to execute a major IT transformation, factoring in such considerations as competing IT and business initiatives, the need to maintain uninterrupted IT service, organizational readiness, leadership, and change management expertise.

These considerations are not meant to be exhaustive but represent the types of analyses that are needed to vet and prepare for partial or full insourcing.

Future Outlook

Outsourcing providers will continue to adapt and evolve to market challenges and buyer behavior to find ways to deliver cost effective high-quality solutions, across all functional domains – this is not only a survival requirement for the IT business units of major offshore companies such as TCS, Wipro, Infosys, and HCL, but also a mandate to protect billion dollar investments in offshore operations made by US companies such as Accenture, IBM, DXC, and Cognizant. Meanwhile, insourcing will continue to gain popularity through political forums and public corporate directives. Repatriating a portion of IT functions will continue its upward trajectory in the near term as a manageable way to make changes quickly in order to build internal knowledge capital and operational flexibility. Full-fledged insourcing will continue to be attempted by bold leaders but will take some time to prove itself as a viable model.